0.1 – 0.5 grams of psilocybin mushrooms every third morning, then off to work or to take care of a task of somekind. That’s the basic equation involved in the micro-dosing method devised by American psychologist James Fadiman.

”It’s almost scary how well it works,” says Mikko, who tried the regimen for six weeks.

Mikko is 40 years old and works in management, a far cry from the stereotypical hippy image attributed to psychedelics enthusiasts. Mikko’s name has been changed for this article, as he does not want to be stigmatized or lose his job for using illegal drugs.

Eighteen months ago Mikko became ill with depression, as one in five Finns statistically do at some stage of life. He was able to work, but says he felt crushed by an overwhelming sense of meaninglessness. He did not want to start taking anti-depressants, put off by the possibly ghastly side-effects and the artificial chemical boost to the pleasure hormone serotonin, which he says did not feel like an ”intuitively right” step to take.

Mikko had read about Fadiman’s micro-dosing approach, poring through articles in scientific journals and reading up on the successes of the process. Mikko’s only other experience with psychedelics had been with LSD at a rave some fifteen years earlier, a trip with very little consequences on his life at large.

”Trying it felt safe because there were people in those circles who were aware of the proper use of psychedelics. But it would be pretty dumb to expect a single tab at a party to change your whole life.”

Two of the most central concepts that affect how someone reacts to a psychedelic trip are known as set and setting – that is, the way the person feels about taking a substance in the moment and the security they feel in the physical environment. In terms of what substances psychedelics may include, this article refers mainly to LSD, psilocybin or ”magic” mushrooms, and the ancient South American brew known as ayahuasca.

”It’s almost scary how well it works.”

The term psychedelics or psychedelia was coined by psychiatrist Humphry Osmond during his correspondence with author Aldous Huxley in the 1950s. This was when studies in LSD and other psychedelics first strode onto the stage of Western society. The word itself is constructed from Greek, meaning ”to reveal the mind”.

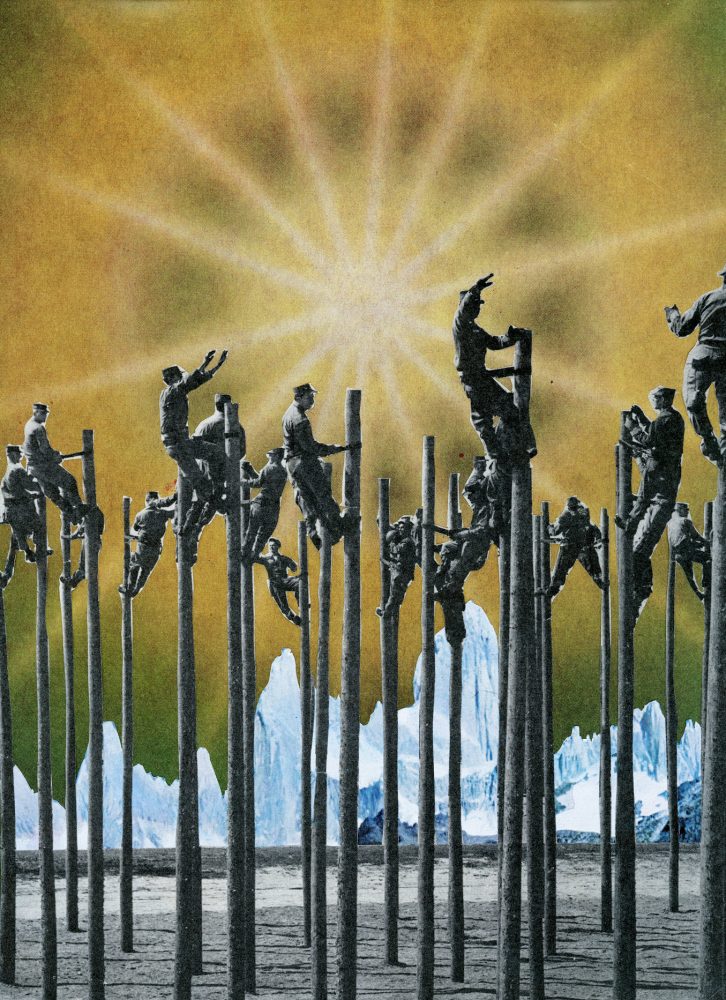

Research shows that psychedelics induce a temporary melting away of the ego, sometimes described as occurring only through meditation, religious experiences, or some other powerful spiritual state. Users commonly report feeling simultaneously connected with all of existence, and yet like the tiniest fraction of a vast otherworldly network. Huxley wrote in his 1954 work The Doors of Perception that one who passes through such portals enters their waking world changed forever.

The amounts of psilocybin or LSD usually used in micro-dosing represent about one fifteenth of what one might take for a medium-intensity trip. Mikko says the effects are almost negligible, bringing a feeling of cheerfulness. But he says the substance is ”much more than just some stimulant”, because it also ”opens you up” by affecting the neuroplasticity of the user’s brain. In states like these, he says, a person suffering from anxiety or depression may find respite from their constant loops of horrible thoughts, and in fact find that they can think more freely and clearly.

”I could observe my own patterns of thinking and behaviour so vividly. And that’s what you need to change such patterns.”

Mikko’s experiences sound splendid on the whole. His ability to learn increased, his creativity was boosted and flow states were easily accessed, he slept and ate better, could see the connections between things and people, and came up with brilliant ideas in meetings.

”Occasionally someone would say, aren’t you in a good mood! It felt mad to think I could have answered that it was because of drugs.”

Mikko emphasizes that micro-dosing mushrooms did not outright cure him of his depression.

”It offered me tools to act in accordance with my wellbeing. These days, if I notice I’m annoyed about something, I can identify the emotion and how to work through it.”

Even while psychedelics are still followed by a pulsing fractal cloud of suspicious hippy madness in the minds of the uninformed, these global substances are also becoming part of the life hacking repertoire of many Silicon Valley tech gurus – not unlike meditation, raw smoothies, and wrist-bound pedometers.

Earlier this year, best-selling non-fiction author Michael Pollan divulged in his book How to Change Your Mind that his very first psychedelic trip was at the ripe age of 60. Pollan says he became convinced of the benefits of what he calls ”white-coat shamanism”: the realization that psychedelics in therapeutic use do not ”mess you up”, but rather help soothe the mind by, for instance, temporarily eradicating the terror of death.

Well-known entrepreneur and angel investor Tim Ferriss claims that almost every Silicon Valley billionaire he knows uses psychedelics regularly. Some of them travel to remote Central American regions to participate in ayahuasca ceremonies, for instance, while knowing the right people can get you a session closer to home – even here in Finland.

The Valley magnates do their part in spreading the message of mind expansion by organizing lectures and seminars on the subject, and by founding organisations that develop and fund research into the properties and effects of psychedelics.

And it isn’t just pharmacological breakthroughs that these groups aspire to. The organisations expect psychedelics to respond to the fiercest problems of the Western information society: the perceived meaninglessness of work and life, the severing of our connection with nature, and the lack of understanding between different groups of people.

To find an era when the middle and elite classes held psychedelics in such high regard, you would have to go to the 1940s through to the end of the 60s. In those times Sandoz, the pharma company that synthesized lysergic acid diethylamide, distributed LSD freely for research purposes. The drug was used to promising effect in combating alcoholism, schizophrenia, obsessive disorders, and other mental health problems in more than 40,000 subjects. Acid was part of the weekend itinerary of many an educated, mid-to-upper-class American.

When actor Cary Grant told Good Housekeeping magazine he had eradicated his alcoholism and identity crisis through ”about a hundred LSD sessions” in the late 50s, patients around the US began clamoring for acid as an aid to their psychotherapy. Alcoholics Anonymous founder Bill Wilson said his own experience of LSD as a treatment for alcoholism was so profound that he even considered adding it to his famous 12 steps.

Soon after in the 1960s, Harvard psychology professor Timothy Leary began to advocate the use of acid to his students as well as audiences outside the classroom. It was through cultural insertions such as this that LSD began to crop up in unexpected circumstances such as campus perties and rock concerts rather than in therapy sessions or other calmer, controlled settings. At the same time the CIA tried to conjure LSD into a sinister mind-control drug, sometimes using unwitting human subjects as guinea pigs in debriefing scenarios.

News and rumors involving psychedelics and their supposed connection with manipulation, violence, and suicide began to spread. In 1966, LSD was declared an illegal substance. President Richard Nixon named Leary the most dangerous man in America.

Despite the moral panic, the results garnered from the experiments were promising. Psychedelics were believed to forever alter psychiatry and mental health care.

When selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (antidepressants known as SSRIs) were invented in the 1980s, they were widely expected to cure depression. That is not what happened; instead, 30 years later depression is more common than ever. It stands to reason that there are more factors at play in depressive illness than mere neurochemical imbalances, and a truly effective antidepressant is yet to be invented.

That’s one reason why psychedelic research has returned in strength in the 21st century.

One study conducted at Johns Hopkins University in Maryland found that psilocybin significantly decreased the existential anguish of test subjects with untreatable cancer. Studies indicating that psychedelics can relieve depression have been done at other universities as well, such as Imperial College London.

However, so far psilocybin research has not produced results that can be considered reliable enough because the test groups have been too small, according to professor of psychiatry Jesper Eklund from the University of Turku in Finland.

Nonetheless, the positive signs have sparked Ekelund’s interest. He is part of a team that is conducting the first truly broad and scientifically viable research into psilocybin mushrooms; the international collaboration includes teams from ten different countries, including Finland, the UK, Germany, and Spain. The subjects chosen for the study have a diagnosed depressive disorder that does not involve psychotic symptoms, and they do not have a history of attempted suicide.

The real work at Turku University Hospital begins in early autumn, 2018. The study will compare the effects of three different doses, the smallest of which is in fact a placebo. The subjects ingest the synthetic psilocybin in a harmonically decorated hospital room with peaceful music playing, and the trip lasts for some 6–8 hours. Support staff provide a sense of safety, but they abstain from actually therapizing during the session.

”Let’s do this right now that we have the chance,” Ekelund says. ”The patient’s safety is guaranteed with close monitoring before and during the session. In such a setting the only risks involved in eating psilocybin have to do with potential dicomfort or anxiety during the experience.”

In three month’s time, the subjects will be interviewed about any possible changes in their daily lives, and whether those changes have been for the better.

”Sometimes I run into an ex-customer a year or so later, and they always seem like a new person. They seem somehow to glow.”

Legalizing psychedelic drugs for medicinal use in Finland is still a remote scenario, but numerous caregivers around the country are already providing ”underground” treatment with psychedelics for those who want it.

Samuli is a practitioner of what he calls ”mushroom massage”. He prefers to discuss his work either during a walk in the woods or in his home rather than over the phone or email. He says he believes that people can only reach a true mutual connection through face-to-face communication.

I visit Samuli’s ascetically furnished apartment, which is decked with numerous thriving house plants. He offers me a cup of strong cocoa with oat milk, the same beverage he offers his customers before they ingest a small amount of domestic psilocybin mushrooms. Samuli also partakes in a micro-dose of the same mushrooms as part of the session. When the effects start to manifest, Samuli begins to gently massage the customer.

This assisted bodily meditation lasts for about five hours, followed by relaxation with some music playing and a conversation, should the customer so wish.

Samuli says he thinks his customers like him because he does not try to pass on any kind of ideology or thought model. Samuli is a 38-year-old university graduate who performs his treatments in his own home. He says that a powerful psychedelic experience some four years ago awoke questions in him about what it means to live a good life, and the desire to dedicate himself to his treatments.

”Mushrooms make finding a bodily connection easier,” he says. ”Customers often tell me they learn to treat their own bodies and themselves better after the session. Sometimes I run into an ex-customer a year or so later, and they always seem like a new person. They seem somehow to glow.”

”Many return for a second or even third session,” Samuli continues. ”My goal is to make myself unnecessary after the third treatment.”

Samuli does not advertise his massage services anywhere. Friends recommend his treatments to friends on the grapevine, and customers keep coming. The treatments are free, and Samuli subsists on donations his customers give him. The all-important mushrooms themselves are either grown, foraged, or otherwise directly procured by Samuli himself.

According to him, psychedelics can have a great positive impact on society in this day and age. He is only half joking when he suggests that Finland should have its own Department of Shamanism.

”Our age is full of sickness and pressures to constantly succeed,” Samuli says. ”Many people don’t know how to be with one another without putting walls up around themselves. I always weigh my words carefully, because psychedelic experiences transcend our linguistic capacity. That’s why it’s hard to talk about a trip without coming off as a bit New-Agey.”

Samuli says he does not believe magic mushrooms to be any universal cure to all the world’s problems, because humans cannot ultimately solve their problems with strategies external to themselves.

”Psychedelics can offer users a deep epiphany, that the happiness of an individual cannot be outsourced to anyone or anything.”

Extensive statistical population studies in Norway and the US have demonstrated that the use of psychedelics does not correlate with increased mental health issues. In fact, those surveyed who had had psychedelic experiences tended to be more psychologically stable than those who had not.

But there are reasons why psychedelics have traditionally been used in communities where a shaman or medicine man controls and guides the utilisation of the substances involved. There is no way to tell beforehand whether a trip will be soaringly heavenly, chaotically hellish, or anything in between.

If a user is not in a safe setting, a terrifying experience may cause them to act erratically, and existing psychological symptoms may even be aggravated.

”Sometimes users or their friends, reacting to a frightening experience, call the emergency services because they don’t know how to deal with a ”bad trip”,” says community organizer and podcast host Henry Vistbacka. He is one of the founding members of ”Psysli”, the Association for Psychedelic Education and Culture, founded in spring 2018.

A year before that another group, the Finnish Association for Psychedelic Research (Psykedeelitutkimusyhdistys ry) was founded to focus on the cutting-edge science of psychedelics. Psysli, for its part, seeks to find ways to address and discuss psychedelics in the culture at large.

”People who have tried psychedelics often talk about how even a frightening experience can transform into something meaningful and eye-opening through a process of integration,” Vistbacka says.

Psysli’s goal is to open up a many-voiced culture of communication about and around psychedelics. Statistics show the use of the psychedelics is becoming more common, even while the subject itself is still on the margins and while the National Institute for Health and Welfare reports that some 2 percent of Finnish respondents have experimented with magic mushrooms of some kind.

Vistbacka says that the understanding of psychedelics needs to increase and expand to allow for more honest dialogue about both the positive and negative sides of the substances in question. He says he believes that psychedelics have the potential to improve self-understanding and self-reflection as well as bridge gaps between different groups of people.

”There is a study starting in the UK at the moment where psychedelics will be administered to a people from different street gangs, apparently to discover if the subsequent experiences increase understanding between people who think very differently.”

”Some Protestant mentality in me that told me this can’t be as good as it feels, the other shoe has to drop sometime, as so often with intoxicants.”

Mikko the micro-doser from before says he doesn’t like the idea of psychedelics being flattened and packaged as nothing but medical products or tools for boosting efficiency. Even with tiny doses, users can introduce what Mikko calls ”an element of wonder” into their lives the likes of which people seldom encounter.

Mikko says he originally planned to micro-dose mushrooms for a few months, but in the end he opted to stop dosing after the six-week regimen – even though he himself says he felt fantastic.

”I was wary of micro-dosing at first, because its long-term effects haven’t been studied. There was also some Protestant mentality in me that told me this can’t be as good as it feels, the other shoe has to drop sometime, as so often with intoxicants.”

Micro-dosing guides online pepper their prose with talk of creativity, excitement, the ability to adapt, understanding others, and the power to take life into one’s own hands. All of these things are necessary in the ever-changing information age.

They have also long been held to be internal characteristics that a person either has or lacks. If cognitive function and happiness can be heightened chemically, who wouldn’t want to hop on that bandwagon of progress?

It seems clear that psychedelics awaken in users the desire to promote the use of such substances, in the same way that principles such as yoga tend to encourage practitioners to practice and teach it.

The mystic realms in contemporary start up psychedelia seems to have at least resulted in some popping keynote speeches, visions of disruption, and some charitability – after all, psychedelics often increase the feeling of being connected to the world.

If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite – William Blake

”I often wonder what psychedelics should be used for,” Mikko muses. ”If the only point is to be more successful in a shitty society, that’s just mixing up the forest and the trees.”

Original article in Finnish. Translated by Kasper Salonen.