May 29th, Mäntyniemi, Helsinki.

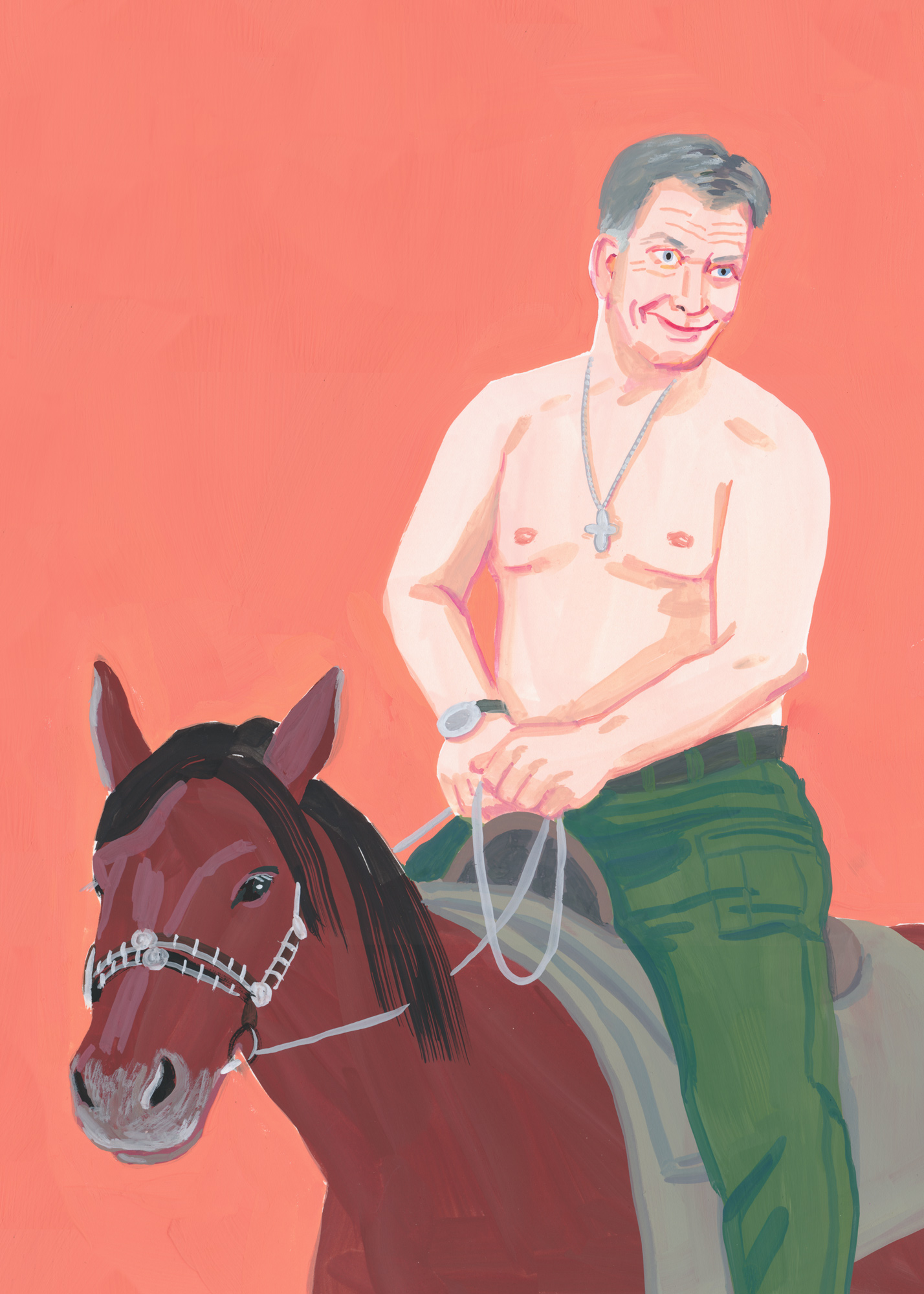

Sauli Niinistö, incumbent President of the Republic of Finland, walks out to meet the press for a briefing at his official residence.

The sound of camera shutters snapping fills the room. The audience is expectant: Niinistö has promised to lay out his ”plans for the future”.

”Right, well, good afternoon,” he begins, as though slightly amused.

”Is it time?”

First Niinistö launches into an update on his work: the ways in which the President’s powers have been curtailed in recent years, especially in domestic politics, and the various tumults in foreign affairs that have arisen during his term.

He also raises the issue of how the President as an institution has withdrawn from so-called party politics.

”How would it feel, then, if a candidate were backed by a constituency association instead?” Niinistö asks the journalists.

A constituency association represents presidential election candidates who do not associate with any political party. A number of media outlets sprang on Niinistö’s decision to resort to one as a ”surprise”, despite speculations of the move having cropped up earlier.

Niinistö’s relationship with his previous affiliate, the National Coalition Party (NCP), had taken a chilly turn especially during Alexander Stubb’s term as chair. News magazine Suomen Kuvalehti reported in spring 2016 that Stubb’s and the President’s relations were ”rotten”. The duo often butted heads when it came to foreign and security policy.

On the other hand, Niinistö’s shift to a voters’ association has been seen to demonstrate an ability to stay in the swim of things. Political science professor Tapio Raunio from the University of Tampere says that similar solutions have often been employed across Europe and the world.

”In the recent Slovenian elections, the incumbent president won a second term by ditching his party and running independently. Practically the same thing happened in Lithuania.”

Raunio says that presidents tend to emphasize their position as representatives of the entire nation, which is why they may also inch (or leap) away from specific parties.

However, this state of affairs has its pitfalls.

Political parties are an institution that the people created for themselves. Despite this, parties now have a significant drawback: the people no longer want to believe in their own creation.

This sucinct summation of the problem is from a 2016 pamphlet drawn up by the Finnish Business and Policy Forum (EVA), written by director Matti Apunen, MP and former media boss Mikael Jungner, and former NCP party secretary Taru Tujunen.

The membership figures of Finnish parties has plummeted in recent years. In 2014 only about 5 percent of Finns belonged to any particular political bloc. And while parties represent ever smaller portions of the electorate, their internal power has centered into smaller groups, further away from the party ranks ”in the field”. In other words, the gulf between voters and leaders has widened.

Political science speaks of a power transition hypothesis, wherein traditional mass parties lose their grip on their members and essentially morph into election machines whose power is held by parliamentary and ministerial groups instead of the party members proper.

Thus, previously broad-based popular movements have changed into leader-driven factions reacting to outward challenges and threats. These groups operate less by invoking the power of their members and more through marketing, PR, and electioneering.

The hypothesis is not Finnish in origin, but researchers such as Tampere University’s Vesa Koskimaa have found it largely applicable here, too.

Finnish attitudes at large have also begun reflecting the gap between decision-makers and the general populace. According to an EVA value survey, as much as 76 percent of Finnish respondents say they believe political parties have drifted away from people’s real, everyday concerns. The Finnish Election Study found in 2009 that only 15 percent of respondents had trust in political parties.

No wonder, then, that a politician vying for popularity wants to represent themselves as an unblemished force external to party politics.

With political faith in crisis, many voters have begun to yearn for strong leaders.

The trend is international. Citizens in many countries have displayed a yen for messiahs ”outside of politics” to bring common sense to the table and ”the voice of the people” into national policy. These supposed redeemers can vary greatly in nature, but they often share the attribute that they do not actually come from outside of politics or the much-derided elite.

Americans got Donald Trump, the French got Emmanuel Macron.

In October, statistics organisation Taloustutkimus put Niinistö’s support figures at a record-breaking 76 percent.

Raunio says Niinistö’s approval rating feels out of place.

”Stats like these are usually found somewhere like Uzbekistan.”

The pining for a strong leader is also seen in people’s hopes and expectations for the President’s use of power. Some 47 percent of EVA survey respondents said they felt that the Finnish head of state doesn’t have enough clout. That figure was at 30 percent a decade ago.

This growing desire is not exactly healthy for a functioning democracy. Researcher Koskimaa writes that modern representative democracy is in essence party democracy. Without party programs and the parliamentary groups to sustain them, the basic mechanism of representative democracy – accountability based on transparency – would become impossible.

But non-accountable political power is precisely the type of rule that seems to mobilize people. The presidential elections have long been considered Finns’ favorite kind of election. In 2012 a whopping 72.8 percent of those eligible cast their vote in the first round the presidential race.

”Power like that does not turn into a political program or political action, and compromises have no place in it. It feels like the power to do good things and take responsibility,” says media researcher Anu Koivunen from the University of Stockholm.

In comparison, last spring just 58.8 percent of those eligible to vote marched to the ballot boxes.

Nevertheless, the President is not a strong leader in Finland. Niinistö has less real power than any of his predecessors. He is the first president who does not participate in EU meetings. Niinistö’s influence is tightly restricted to the Council of State’s ministerial committee on foreign and security policy, which he runs.

To understand the President’s prerogatives, we have to look back to the civil war. When it ended in 1918, confrontation and distrust were rife in the Finnish political elite. Relations between the left and right were septic, and the Whites who won the war wanted to make sure that a socialist revolution could not happen through parliamentary measures.

That is why the government was backed by a head of state with armfuls of power: the President. Finland’s constitutional rule of law was in fact called ”semi-presidential” before the reform of the 2000s.

20th century presidents used power according to need. Some where more moderate in domestic policy, but Urho Kekkonen, who took up the mantle in 1956, was not among them. Kekkonen ruled Finland for 25 years with what political science professor Heikki Peloheimo calls absolute power and had a higher standing in domestic politics than any other semi-presidential president.

When a degree of trust returned in the 1960s and 70s, the time was ripe for parliamentizing the President’s powers. Gone were the days of a President who appointed governments, broke apart parliaments, and imposed premature elections on personal whims.

What was left to the President was a final say in foreign politics – together with the Council of State.

A strictured playing field may have increased Niinistö’s popularity, as he hasn’t had to face scandals or navigate domestic policy labyrinths – unlike those who came before him. When daily Helsingin Sanomat in November analyzed Niinistö’s support, it wrote that his success was largely based on staying out of the spotlight on domestic concerns but responding steadfastly to foreign and security policy expectations.

Another reason may be that Niinistö’s power is not public. Only insiders are aware of what goes on in cabinet committee discussions, and the media is powerless to penetrate the actions of ministerial groups.

The media’s inabilty to critically assess the President’s work may explain some of Niinistö’s sky-high ratings, Raunio says.

”If the President’s actions were scrutinized more closely, and if the media were to offer alternative ways to fulfill the President’s duties, it may be that the statistics would dip.”

There would certainly be no lack of phenomena to examine. Suomen Kuvalehti wrote in October, for instance, that Niinistö has been stronger as President than his limited powers would imply. He has spontaneously stepped up to the foreign policy plate more effectively than the government, even though the two institutions should theoretically be matched in power.

The constitution says that foreign policy in Finland is ”directed by the President of the Republic in co-operation with the Government”, but Niinistö has announced that he has added a pause after the President part – as if to signify who is really at the top of the pyramid.

This has gone over fine with the government. Prime Minister Juha Sipilä’s inexperience has kept him away from foreign affairs, and the NCP (which criticised previous president Tarja Halonen) has not attempted to run afoul of its erstwhile golden boy Niinistö.

Centre Party member Harriet Lonka, however, came down hard on Niinistö’s use of power in a February edition of weekly paper Suomenmaa.

”The President has hijacked the Cabinet Committee,” she intoned.

Lonka made specific reference to how the Cabinet Committee only gets together as the Security Policy body, with the President as its head.

”Its basic nature in our parliamentary democracy is that it should function without the President, lead by the Prime Minister.”

Another thing that has made media scrutiny difficult is that Niinistö has not been especially forthright about his own use of power or his agenda with the media.

In summer 2016, Niinistö suggested to his counterpart to the east Vladimir Putin that Russian military aircraft should keep their transponders on during official flights. Helsingin Sanomat wrote in July that the President’s notion had caused alarm and had been thought up in opposition to common Finnish foreign policy.

Instead of, say, commenting on the allegations directly to the paper, Niinistö started a blog and published a post where he questioned the article’s position.

In other words, the President founded a media outlet of his own and reserved the right to define the sequence of events and the nature of the subjects discussed as he saw fit. It was a skillful move in a time when traditional media enjoys less and less trust as it is.

”In times like these, when the media is seen as a wielder of power like any other authority, [in posting in his blog] the President shows himself to be an agent who eyes the so-called mainstream media with suspicion along with the rest of the people,” Koivunen says.

Niinistö last declined an interview invitation from Helsingin Sanomat a few weeks ago, when the paper did a piece on the Nato positions of the rest of the presidential candidates.

Niinistö’s attitude seems arrogant, but Helsingin Sanomat would have a hard time saying that outright. Criticizing a beloved president would almost certainly herald doom, even for the most widely circulated newspaper in the country.

Niinistö’s trick of seeming to place himself outside of party politics worked like a charm. Over the summer his team gathered more than 156,000 signatures for his voters’ association – almost eight times the required amount. Fans of President Sauli flocked to Finnish market squares and shopping malls to secure as many supporters for his potential second term as they could.

In reality, the voters’ association is something of a gimmick with a lot riding on image alone. On the campaign’s website visitors are welcomed to the ”nonaligned” Sauli Niinistö movement – even though the initiative’s management is chock-full of National Coalition Party heavyweights.

Campaign manager Pete Pokkinen is a long-time special adviser to NCP ministers, operations chief Sanna Kalinen used to be the party’s organization manager, and the association’s legal representative Heikki A. Ollila is a former NCP MP. Not only that, but Ollila together with Niinistö and politician Kari Häkämies used to be collectively known as the ”Hewey, Dewey and Louie” of Finnish Parliament in the 1980s.

None of this can erase the fact that founding the constituency association created the impression that the coming presidential elections will be pitting a bevy of party-backed politicos with a seemingly cleaner ”candidate of the people”. Pragmatic political rhetoric emphasizes the counterbalance of a neutral, sensible, and above all non-ideological Mr. or Mrs. Fixit and an ideologically blinded opposition.

Such rhetoric fits in well with the tradition of Finnish foreign policy, where basing things in sense has been quite popular.

”There are certainly indications that make it seem as if the whole nation as a single entity would be ready to vote Niinistö back in,” Koivunen says.

Researcher Koivunen reiterates that for as long as the presidential election has been conducted as a national election, the process has always run into a second round of votes. It’s by then at the latest that a polarization effect has been created to show just how worlds apart the last two standing candidates appear to be.

This might be the first time since national Finnish elections began that a second round may not be needed. Niinistö may be able to let the other candidates squabble among themselves, relegate himself to the sidelines, and still get elected by a landslide. In his second term he would be able to keep exercising his power without having to explain himself or his agendas to anyone whatsoever.

Professor Raunio brings up the point that at its core, politics is about compromises and the actions of the many through collectives such as parties and civic organizations.

”This coming election is producing an upside-down view of politics. That’s not good.”

This article used the following books as its sources: Puhun niin totta kuin osaan – Politiikka faktojen jälkeen (Docendo, 2017), edited by Johanna Vuorelma and Paul-Erik Korvela; Poliittinen valta Suomessa (Vastapaino, 2017), edited by Mari K. Niemi, Tapani Raunio, and Ilkka Ruostetsaari; and Suomen puolueet – Vapauden ajasta maailmantuskaan (Vastapaino, 2015) by Rauli Mickelsson.

Translated by Kasper Salonen.