A smooth sea never made a sailor.

A sailing-themed motivational poster hangs imposingly on the wall of Finnish technology company Jolla’s break room. In Finnish, Jolla translates as ‘dinghy’ – and the company is not short on seafaring puns.

The poster offers a self-deprecating reminder: …Nor buried one.

The thought must have crossed the minds of Jolla’s employees. Jolla is known as a company that has had its fair share of difficulties. Stormy times surely offered some valuable lessons, but were they worth risking sinking the whole ship?

Jolla CEO Sami Pienimäki steps into the break room looking exhausted. The dark circles under his eyes might be caused by travel fatigue, as Pienimäki has just returned from Hong Kong, where he spends a significant part of the year. Or they might be because Pienimäki has been in the midst of Jolla’s tumultuous journey.

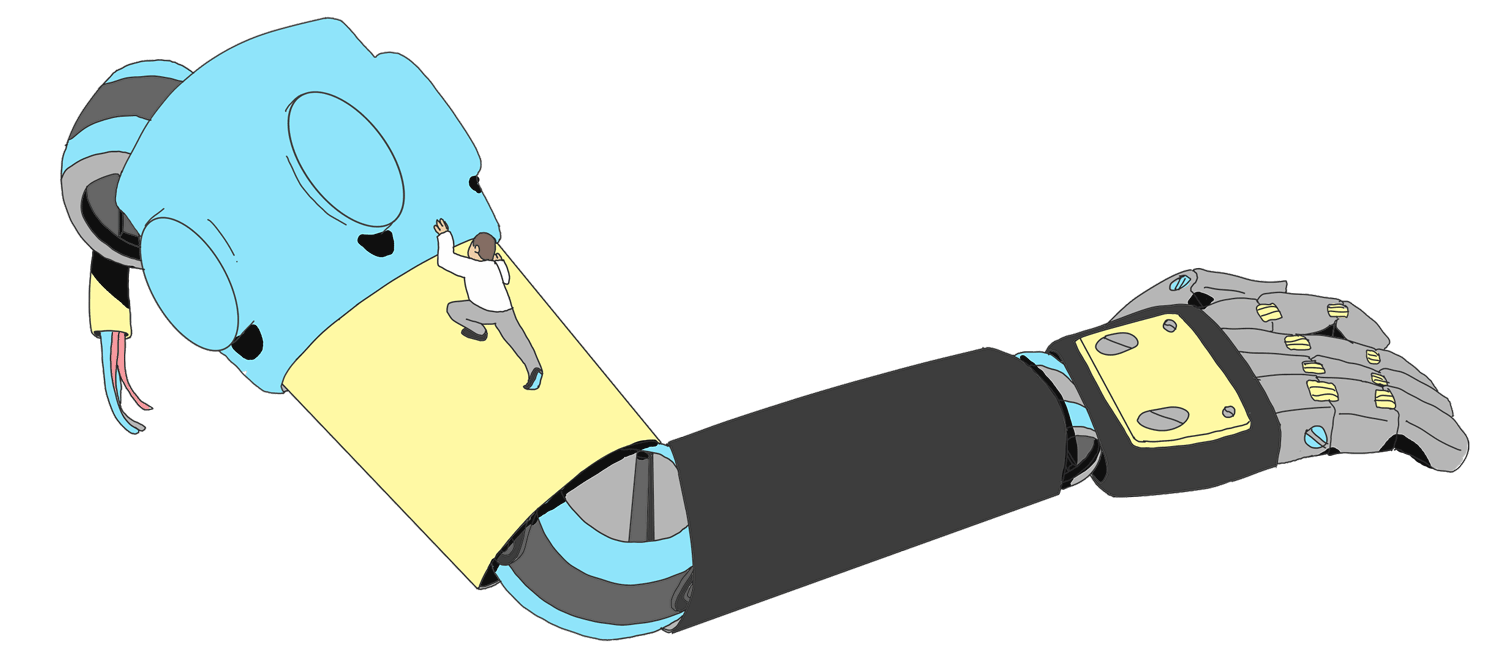

Jolla was born out of anxiety. In 2011, Nokia’s new CEO Stephen Elop announced that the company would abandon its MeeGo operating system and adopt Windows systems in all its mobile devices instead.

When the news broke, Pienimäki was leading MeeGo’s product design team. A few months later he took the reins of Nokia’s Bridge program. The program was supposed to ease the transition of those laid-off into new ventures, including helping ex-employees start their own businesses.

Consequently, Pienimäki found himself becoming an entrepreneur. Pienimäki wanted to salvage what was left of MeeGo, a reliable software that had built itself a loyal fan base over the years.

”Something had to be done. We couldn’t just leave it there,” Pienimäki says.

Pienimäki’s vision was shared by Antti Saarnio, Marc Dillon and Stefano Masconi, and soon the group founded Jolla. Its goal was to finish what Nokia had started and polish the product Stephen Elop didn’t believe in to perfection.

The project quickly gained media traction and managed to build social media hype before they had even launched their first product. In the beginning, the company had its audience’s sympathy on its side; they were viewed as a small player trying to make their mark in an industry full of giants, by building a new phone out of what seemed like nothing. The project sounded plausible: it had an acclaimed operating system funded and developed by tech titans like Microsoft and Intel.

When Nokia announced it would sell its mobile phone business – Finland’s pride – to Microsoft in 2013, Jolla was hailed as a saviour to the national identity crisis that ensued. The company was Finland’s last chance at regaining old glory in an industry that had once saved the country from the grips of a recession.

Jolla represented everything that politicians had assured us would save Finland this time around: new innovations, start-up spirit and Finnish work ethic.

In 2012 Jolla introduced its first operating system; MeeGo had been renamed Sailfish. The following year, with newfound confidence, Jolla stepped onto the main stage of Slush, Europe’s leading start-up event, to announce it would release its first mobile phones a few weeks later in a pop up store in central Helsinki. On the day of the launch, 450 people showed up to get their hands on the new phone.

Next, in 2014, Jolla released its very first tablet, with a crowdfunding campaign that exceeded all expectations.

Then everything started going wrong.

The majority of tablet buyers still haven’t seen the finished product, and most likely never will.

Only a year after the tablet launch, Jolla froze production and delivery entirely.

”It was just one problem piling up after another,” Pienimäki explains.

Initially it was minor technical mishaps in production that took months to adjust. In the end, fixing a small problem here and another there ended up burning more money than Jolla had to spend, and Pienimäki had to pull the plug before the company lost every dime it had.

Pienimäki was appointed CEO of the company this year, and his main responsibility has been answering disappointed customers. Jolla is only halfway through paying back all of its tablet reclamations.

Jolla’s troubles started long before its disastrous venture into the tablet market: consumers weren’t buying the hype around Jolla’s phones. Mobile sales had stayed sluggishly far from the announced goal of hundreds of thousands of devices.

Jolla failed to cash in on their initial publicity to reach even their modest goal of not even a percent of the total smartphone market.

Jolla has refused to share exact sales figures. Pienimäki too stays mum, but confirms that hundreds of thousands became some mere tens of thousands. The company took a big financial hit, and the past two years have left the company with a yearly deficit of over 10 million euros.

One explanation offered for Jolla’s stagnant sales figures is that the phone released was consciously unfinished. Many consumers took this to mean that the phone was, well, rubbish.

American technology news site The Verge wrote that Jolla’s only strength was the benevolence of Nokia fans and those wanting to support grassroots projects. Renowned technology blog Engadget reviewed the company’s products as having ”good intentions, bad delivery”. The largest daily paper in the Nordics, Helsingin Sanomat, opined that Jolla was still far too rough around the edges.

In its early days, the phone could not be used horizontally and its battery would drain out in only a few hours. Regular updates fixed some of the problems, but weren’t enough. Using apps was clumsy. The selection of apps made exclusively for Jolla’s Sailfish was embarrassingly small, and those made for Android were generally too flaky.

Professor of Usability and User Interfaces at Aalto University Marko Nieminen believes that some users lost their patience with the phone quickly and swapped it for another. Bad first impressions had a fatal impact on sales figures.

Sami Pienimäki still believes launching an unfinished phone was the right call.

”Launching the first product is a very important moment for any company. The world is full of products that are only 95 percent ready,” he says.

He believes stretching the launch by even six months could have ”killed the whole agenda”.

Either way, after the phone flop and the tablet tragedy, Jolla’s promising hype effectively died out.

Regular phone users weren’t interested in sticking around long enough to fall in love with Sailfish, when competitors’ Android and Apple’s iOS systems were already fine-tuned and fully operational.

And yet, the worst was still to come.

Over 55 million euros’ worth of venture capital financing is the sole reason Jolla is still up and running. So far this money has been used to pay off debt.

”We were surprised by how long and how much effort it actually takes to become profitable in this industry. It’s been a bigger burden and longer journey than we expected,” Pienimäki says.

Most of Jolla’s financers are private investors from China, Russia and Europe. Russian businessman Grigory Berezkin invested 9 million euros in Jolla last year. Additionally, the Finnish funding agency for technology and innovation, Tekes, has supported the company with over 8 million euros – a significant sum for a fledgling company.

Pienimäki emphasizes that the money from Tekes is a loan for product development, and Jolla is paying it back diligently. The loan was granted due to Jolla’s roster of other investors.

November 2015, just a day after Slush, brought bad news: an important investor announced they could not make their decision on whether to continue funding on time.

”We were in full-blown crisis mode. Based on previous experiences, we presumed everything was fine. We still don’t know what happened,” Pienimäki says.

Jolla had to file itself into debt restructuring, but just a month later the company announced it had secured funding after all.

The good news was short-lived. Financial woes have forced Jolla to lay off half of its 100-strong staff, and relocate from their central Helsinki offices. Two of its four founders, Dillon and Mosconi, left last year.

This year isn’t looking any better, and Pienimäki is prepared for significant losses.

Ironically, Jolla has now followed its predecessor’s path and revamped its entire business strategy.

Jolla’s newest incarnation is no longer attempting to attract customers with its own products, but is focused on promoting its Sailfish operating system to other mobile phone producers. Potential adopters include Indian Intex and American-Chinese Turing Robotics. Fittingly, the latter is producing its phones in Nokia’s old factories in Finland.

Professor Marko Nieminen from Aalto University lists Sailfish’s strengths: its open source code is easily customized, and it has multitasking features that are far more sophisticated than those of competitors. Being independent from tech giants like Apple and Google, Sailfish has developed exceptional information security features.

However, phones equipped with Sailfish haven’t been roaring successes, as the system does not have clear advantages over Android or Apple’s iOS. Jolla, however, is hunting for bigger game: taking over digital ecosystems and Russia.

A digital ecosystem is a world where current information technologies, like devices, operating systems, apps, websites and users are all connected to each other. Western digital ecosystems are dominated by American tech firms like Apple, Google, Microsoft, Facebook and Amazon.This is something Russia is keen to change, and Jolla wants to be the solution.

Russia and China have developed their own alternatives to American firms, such as China’s ”Facebook” Tencent or Russia’s ”Google” Yandex. Jolla’s Sami Pienimäki believes the American operating system hegemony is also coming to an end. Take airplanes, for example.

”Why was Airbus founded? At first, there were only Americans: McDonnel Douglas and Boeing. Then France, Germany and the United Kingdom realized they can’t be dependent on them forever,” Pienimäki says.

The thought of Jolla being the base for Russian or Chinese mobile operating systems may seem absurd – overly ambitious at best – but there are signs of an Airbus phenomenon. Russia’s Minister of Communications and Mass Media Nikolai Nikiforov has declared that the government aims to reduce American operating systems in Russia from the current 95 percent to 50 percent by 2025.

Nikiforov has publicly praised Sailfish and discussed developing the system on a larger scale at a meeting for BRICS countries, Brazil, India, China and South Africa. A Russian company called Open Mobile Platform has, without much fanfare, licensed Sailfish and hired programmers to develop a Russian OS based on the system.

Naturally, Marko Nieminen thinks this development is highly desirable. If Russia does not build its operating systems on Sailfish, then it will choose another non-American program. The thing is, there really aren’t that many options. Sailfish’s biggest competition Tizen, (also developed from MeeGo), is funded by South Korean Samsung and American Intel.

If Jolla could access Russia’s massive market, politics would come second. Pienimäki dodges questions about the ethics of doing business with Russia, a country upon which the European Union has imposed sanctions. He stresses that Russia is just one of the markets Jolla is approaching.

Mistakes are a gift. Those four words are repeated piously time after time in the start-up world. Even Finnish Nobel laureate Bengt Holmström is a believer.

Nonetheless, it is still virtually impossible to find a company which would publicly subscribe to this thought in times of distress.

Jolla is no exception, and the company has steered clear of the limelight in recent years. CEO Pienimäki believes that times will be drastically different in two to three years.

”Our goal is for as many markets as possible to adopt Sailfish into their digital ecosystems.”

If it were up to Pienimäki, one of these markets would be his native Finland. In a different reality, the Finnish government would aim to build its own digital ecosystem. A national digital ecosystem could potentially be beneficial in ways we cannot yet imagine, Pienimäki says. However, his and Jolla’s enthusiasm hasn’t caught on.

”There is a lot of talk about creating a comprehensive digital society, but it feels like people are forgetting the basics. It’s short-sighted to license everything, even basic technology, from big American firms and forget about local technology and independence.”

Translated by Melissa Heikkilä.